Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer and sexual assault lawyer serving Calgary, Okotoks, Airdrie, Strathmore, Cochrane, Canmore, Didsbury, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge and Turner Valley.

A recovering drug addict in New York is suing a Quebec drug dealer, nicknamed the King of Pot, for flooding the United States with over a billion dollars worth of marijuana, claiming it was his drugs that made her an addict.

The King of Pot, whose real name is Jimmy Cournoyer, is serving a 27-year prison sentence in the United States as a result of a 2014 conviction in which he was dubbed the biggest pot dealer in New York City history.

The recovering addict suing Cournoyer is Conseuelo Barbetta, who told a New York City judge that at the peak of her addiction, she was not sober for more than a minute over a four-year period. She is suing for $5 million in damages as a result of her 18 years of substance abuse.

“Both me and Cournoyer were between New York and California during the time my addiction was at its worst and his business was at its best.”

Despite his being a large-scale drug trafficker, there is one little hiccup in the lawsuit – Ms. Barbetta has never met Cournoyer, has no idea if the drugs she consumed were from him and only heard of him in the newspaper.

Despite being given significant leeway as she was self-represented, her motion was dismissed by Judge Brian Cogan, the same judge who oversaw the massive 2019 trial against Mexican drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman.

Judge Cogan found that the plaintiff was merely guessing that Cournoyer had a hand in her illegal drug purchases which doesn’t rise to the level required to advance a claim.

While the suit was dismissed, it is of interest given that lawsuits against drug dealers are starting to arise. The lawsuit was as a result of newly passed legislation in the USA called the Drug Dealer Liability Act, which allows consumer of illegal drugs to seek civil damages against those selling the substances.

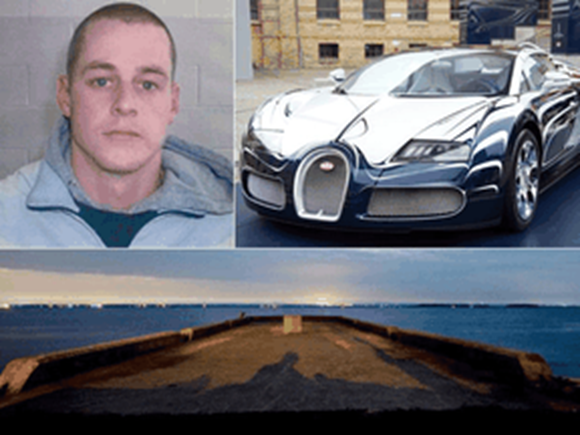

The King of Pot – Jimmy Cournoyer

US prosecutors said Cournoyer was a masterful drug baron who went from growing a small amount of marijuana in his Laval, Quebec apartment as a teenager to running a massive international drug consortium.

Before being arrested, he lived a playboy lifestyle, driving exotic sportscars, entertaining friends at a rented island and partying with celebrities and his model girlfriend. It was all brought down by a scorned ex-girlfriend.

One day in January 2007, the disgruntled ex-girlfriend walked unprompted into the district office of the Drug Enforcement Administration on Long Island. Sitting down with an agent, she bitterly gave vent: Her former boyfriend, the father of her child, was selling weed.

As a rule, the drug agency isn’t in the business of settling romantic scores, but the woman, who had shown up with her child in tow, was adamant that her onetime lover was a major player in the city’s wholesale marijuana trade. A group of federal agents started looking into the man.

What began that day with a woman scorned unfolded over the next seven years into an investigation that went beyond the wildest imaginings of the agents assigned to it, an elaborate case that led to the discovery, and subsequent arrest, of a surprising quarry: an international criminal who is now described as the biggest marijuana dealer in New York City history.

That man, a French Canadian playboy named Jimmy Cournoyer, spent almost a decade selling high-grade marijuana in the city, trafficking the drug through a sprawling operation that moved from fields and factories in western Canada, through staging plants in suburban Montreal, across the United States border at an Indian reservation and finally south to a network of distributors in New York. Along the way, Mr. Cournoyer, a martial-arts enthusiast with a taste for fast cars, oversaw an unlikely ensemble of underlings, a company of criminals that came to include Native American smugglers, Hells Angels, Mexican money launderers, a clothier turned cocaine dealer in Southern California and a preppy, Polo-wearing Staten Island gangster.

It all came to an end three weeks ago, when Cournoyer was sentenced in Brooklyn to 27 years in federal prison, finally bringing to a close the investigation that emerged in 2007 from that domestic dispute.

The size and sophistication of his fallen empire were unprecedented, those who chased him say. Starting in the mid-2000s, Mr. Cournoyer managed the shipment of man-size bales of hydroponically grown pot across the border on motorboats and snowmobiles. Nearly $1 billion of his cash was laundered through the Sinaloa drug cartel or was ferried back to Canada in pickup trucks equipped with secret traps in their radios and gas tanks.

“We never saw anything like this guy before,” said Steven L. Tiscione, a federal prosecutor in New York who supervised the task force that broke the case. “In terms of his longevity and scope, and the connections he had around the world, nothing, nobody, comes close.”

At the height of his success, Mr. Cournoyer, who is now 34 and is awaiting placement in the federal prison system, drove a Porsche Cayenne and a $2 million limited-edition Bugatti Veyron. He was friends with Georges St. Pierre, a mixed-martial arts fighter, and dated a lingerie model. His social circle was configured such that once, on a trip to Ibiza, he attended the same party as Leonardo DiCaprio.

These circumstances could not have been more different from those of his pursuers on the task force, composed of local detectives, career federal agents and government prosecutors like Mr. Tiscione. The task force, however, had a lead, and within a year of receiving the woman’s complaint, the Queens dealer, who was caught selling drugs, was facing prosecution and became an informant.

One piece of the information he provided was the alias of his Canadian supplier, a man known as Cosmo, whose name, he said, derived from his residence in the Cité Cosmo, a luxury condominium in the Montreal suburb of Laval. Mr. Tiscione and his team eventually learned Cosmo’s real name by eavesdropping on his network with wiretaps and by putting pressure on other dealers, but they were unaware of his lengthy history until they contacted the authorities in Laval. The Canadians described Mr. Cournoyer as a seasoned trafficker whose criminal career had begun at age 18, when he and his brother Joey were arrested with a stash of 11 marijuana plants at their apartment.

In 1998, Mr. Cournoyer pleaded guilty in that case and was sentenced to probation. But two years later, he was caught again, selling marijuana out of his Jeep at the Kanesatake Mohawk reservation, a half-hour’s drive from Laval. Although he pleaded guilty in that case, too, he escaped a serious prison term. He was arrested, for a third time, only 12 months later. On that occasion, Mr. Cournoyer had checked into a Hilton in Toronto, planning to sell 10,000 Ecstasy pills to a customer for $65,000. The customer turned out to be an undercover agent. As he tried to flee, Mr. Cournoyer was captured, despite, court papers say, brandishing a handgun loaded with armor-piercing bullets.

The lesson he learned from prison that time was perhaps not what the authorities intended. As Mr. Tiscione would later write in a legal memorandum, “Determined to never again be found in the compromising position of physically touching narcotics, Cournoyer began expanding his roster of associates and installing additional layers of subordinates between himself” and the drugs.

Among those subordinates was Mario Racine, a fellow Canadian, whom Mr. Cournoyer sent to the United States in the early 2000s, court papers say, to manage the increasingly giant loads of marijuana flowing across the border. Mr. Cournoyer had met Mr. Racine through Mr. Racine’s sister, Amelia, the lingerie model whom he dated for several years. Mr. Racine organized the outfit’s East Coast distribution. The biggest distributors were generally given up to 200 pounds of marijuana at a time, with brand names like Sour Diesel, which they then resold in pound quantities to smaller retail salesmen.

Another top lieutenant was Patrick Paisse, a one-legged Québécois who helped Mr. Cournoyer arrange a deal with the Hells Angels to drive huge loads of pot from fields in British Columbia and greenhouse factories equipped with charcoal air filters and off-the-grid power systems across the border, hidden beneath the tarps of tractor-trailers.

Mr. Paisse also helped him make contact with a network of Native American smugglers at the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation, who moved their own loads south across the St. Lawrence River, on small boats during temperate months and on snowmobiles in winter.

The reservation, which sits along the border of New York State and Canada, was a perfect corridor for shipping drugs to American buyers, and the Native residents who worked with Mr. Paisse had long experience in moving contraband, like firearms and cigarettes, through its skein of private docks. One of the Natives who took part, Kenneth Cree, lived in an immense house studded with surveillance cameras.

Before long, court papers say, the trafficking operation was “pumping regular shipments of high-grade marijuana into the United States.” But in 2004, one of Mr. Cournoyer’s top New York distributors stole a load worth more than $1 million, souring relations with the Hells Angels, who lost out on the fee to transport the drugs.

That same year, Mr. Cournoyer crashed his Porsche, killing a passenger, and was imprisoned on charges related to the death. Although he served only a year, he was forced upon his release to live in a halfway house in Montreal. In his absence, his enterprise had fallen into “tatters,” Mr. Tiscione said. But Mr. Cournoyer managed to rebuild it, meeting secretly with associates during hurried rendezvous in the Montreal subway and while on work release from the halfway house, where — industrious as ever — he had found a job driving an elderly woman to her medical appointments.

The operation was flourishing again by late 2007, when the Drug Enforcement Administration began to make inroads in its investigation.

Unbeknown to the task force in New York, a separate team from the drug agency had around that time started a sting operation against money launderers working with Mexican drug cartels. That fall, for instance, an undercover agent posing as a cartel financier had persuaded Mr. Racine, Mr. Cournoyer’s New York manager and one of his closest partners, to give him $94,000 in marijuana profits, promising to reinvest — and cleanse — the money through the purchase of cocaine.

Though the agents in New York could have had Mr. Racine arrested at that point, they chose to let him go, albeit under surveillance, to preserve the investigation. Mr. Tiscione’s task force knew that Mr. Cournoyer already had ties to the Hells Angels, the Mohawk smugglers and the Rizzuto crime family of Montreal, which ran large swaths of that city’s drug trade. Now the task force realized that the outfit also had a Mexican component, and set about to infiltrate that corner of the business.

It took a few years, but by 2010 the agents had persuaded Mr. Cree, who was facing a lengthy prison term, to work as an informant. According to Mr. Tiscione, they had Mr. Cree engineer a money drop at a safe house only blocks from the Brooklyn federal courthouse. Calling Mr. Cournoyer one day, Mr. Cree offered to oversee the shipment of $200,000 from New York to Los Angeles for a 6 percent commission. As part of the deal, he was given the phone number of a man in California who would take the cash on arrival.

When undercover agents in Los Angeles called that number, they reached a man named Alessandro Taloni. Mr. Taloni, court papers say, was an Italian-born associate of the Rizzutos who also served as Mr. Cournoyer’s manager for West Coast operations. He ran a lucrative money-laundering business out west, using dirty cash to buy cocaine from the Sinaloa drug cartel while maintaining his sideline as a vendor of high-end hair-care products. A former salesman at a Montreal men’s shop, Mr. Taloni had been charged a decade earlier with threatening to kill the owner of a rival clothing store in an attempt to cow the competition.

Now the agents watched Mr. Taloni pick up the money that a courier hired by Mr. Cree had flown to California on a private jet. After fetching the delivery, Mr. Taloni, with the surveillance team in tow, continued on in his Mercedes-Benz to the Beverly Hills Hotel. There, court papers say, he met another man, who handed him a suitcase with a second cache of money. This was cause enough for the agents on his tail to stop him and later to search his apartment, where they found 49 kilograms of plastic-wrapped cocaine and nearly $1 million, all of it in cash.

Almost from the moment their case began, Mr. Tiscione and the task force had relied on old-fashioned, grind-it-out police work. Now, however, the task force caught a lucky, and unexpected, break.

Dominick Curatola was a muralist turned house painter turned pot dealer, living on Long Island. He was a minor player, but he still had connections; his boss in Canada was a close associate of Mr. Cournoyer.

One day in mid-November 2010, Mr. Curatola’s usual money launderer was unavailable, and he found himself in need of someone to help him move a cash shipment to Canada. According to Mr. Tiscione, Mr. Cournoyer volunteered his own man for the job, a Honduras-born trafficker named José Castillo-Medina.

Mr. Castillo-Medina, three years earlier, was involved in the cartel money-laundering operation with Mr. Racine. Now he was at it again, according to court papers, dispatching a woman named Elizabeth Jennings to meet with Mr. Curatola in the parking lot of a Staples store in Brooklyn. Even the government acknowledges that this was a onetime favor; Mr. Castillo-Medina simply picked the wrong day to be helpful.

As it happened, a different team of federal drug agents on Long Island had for weeks been following Mr. Curatola and were there that day when Ms. Jennings took from him a black Express shopping bag filled with $169,000, then hurried back to her apartment in Brooklyn to walk her dog. They were also there when Mr. Castillo-Medina arrived at the apartment later. When the agents searched the place, they found bags of marijuana, two narcotics scales, $500,000 in cash and coded ledgers indicating deals of more than $4 million between a man named Primo and a large New York distributor referred to only as Staten Island.

It took a wiretap investigation to finally determine that “Primo” was Mr. Castillo-Medina and that “Staten Island” was a Bonanno crime family associate named John Venizelos. Besides selling millions of dollars’ worth of marijuana, court papers say, Mr. Venizelos, who favored horn-rim glasses and Ralph Lauren pastels, managed a Mafia-owned strip club, Jaguars 3.

Once the task force had identified Mr. Venizelos, federal agents descended on his house on Staten Island and then on his parents’ house nearby. They seized more marijuana, more narcotics scales and more ledgers, as well as a shotgun and a loaded Glock.

They also seized an encrypted BlackBerry, Mr. Tiscione said, which was the device of choice for the Cournoyer outfit. Given that a number of the boss’s men were already in custody, the agents were especially concerned by a message that Mr. Venizelos had sent just days before his own arrest, to a partner who had been captured and was under pressure to cooperate with the task force.

“U just got to hope they never find out u said a word, seriously bro,” Mr. Venizelos wrote. He added, chillingly, that Mr. Cournoyer kept on hand a $2 million slush fund to pay for the murder of anyone who crossed him.

The flight to Mexico left Canada at 6 a.m. Among the passengers onboard that day, Feb. 16, 2012, was Jimmy Cournoyer.

After five years of flipping witnesses, listening to wiretaps and conducting secret stings, Mr. Tiscione and his team had finally gotten a Brooklyn grand jury to indict Mr. Cournoyer on drug conspiracy charges on Jan. 20, 2012. A month later, the newly minted defendant tried to abscond to Cancun.

Landing at the airport, he was immediately detained by the Mexican authorities. Pointing to a “red notice” alert issued in his name by Interpol, they refused to let him in.

Although Mexican officials tried three times to put Mr. Cournoyer on a plane to the United States, he refused to go, threatening, court papers say, to “harm the captain and the crew.” Finally, he was hooded and escorted onto a flight to Houston.

In the year that followed his arrest, Mr. Cournoyer and his lawyer, Gerald J. McMahon, disputed his removal from Mexico as “a forcible abduction” and tried to have the sprawling case against him dismissed. But as the evidence mounted, Mr. Cournoyer pleaded guilty in May 2013, just days before his trial was scheduled to begin in federal court in Brooklyn.

Even though marijuana is increasingly legalized and, unlike methamphetamine or heroin, rarely makes for sensational headlines, prosecutors argued in a sentencing memorandum that Mr. Cournoyer’s operation was a violent one and that it led to the enrichment of other criminal syndicates. His friends and family countered with letters to the Brooklyn court praising Mr. Cournoyer’s good nature and blaming his criminal exploits on the trauma he suffered at age 16, when his father left his family.

“That’s when I started to see a change in my son,” his mother, Linda Bremer, wrote. “He wasn’t focused anymore. He was kind of a rebel. I thought it was because of the divorce.”

Whatever his psychic pain, Jimmy Cournoyer had been driven all along by a singular passion, his lawyer said in an interview: a love of money.

“There’s a lot of weed smokers here on the Eastern Seaboard, a lot of them,” Mr. McMahon explained. “That’s why he came to New York, for the capitalist markets. It was basically a Karl Marx kind of thing.”

Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer based in Calgary. If you have been charged with a criminal offence or are a suspect in a criminal investigation, call today for a free, no obligation consultation.