BLOG

Elements of the offence: Mens Rea

Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer serving Calgary, Okotoks, Airdrie, Strathmore, Cochrane, Canmore, Didsbury, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge, Grand Prairie and Turner Valley.

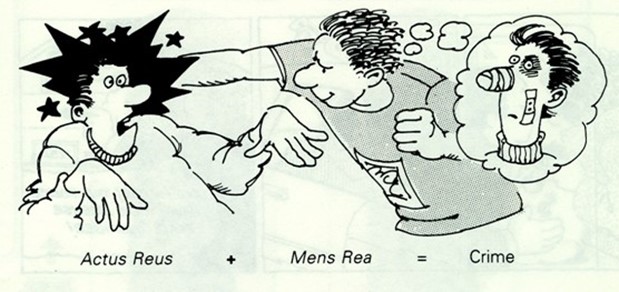

In Canada, to be found guilty of a criminal offence, the Crown must prove, among other things, that the accused committed the guilty act, and that the accused possessed a “guilty mind” when committing the guilty act. In criminal law, the guilty act is called actus reus. The “guilty mind” is called mens rea. Actus reus and mens rea are commonly referred to as elements of the offence or ingredients of the offence.

This blog post focuses on mens rea – the “guilty mind.” Some crimes require the Crown to prove subjective mens rea, while others require proof of objective mens rea.

Subjective Mens Rea

Subjective mens rea is concerned about what is going on in the individual’s mind at the time that the guilty act occurs. When an individual is charged with a subjective mens rea crime, the Crown must satisfy the judge that the accused subjectively intended to commit the prohibited act.

There are four types of subjective mens rea – intent, knowledge, wilfull blindness, and recklessness.

Intent

Intent focuses on an individual’s desire to bring about a specific consequence. In terms of criminal offences, intent focuses on the accused’s desire to commit the guilty act. Proving someone’s “desire” to commit the guilty act (mens rea) is more difficult than proving that someone did the guilty act. For example, if someone is shopping and they try on a hat and leave the store without taking the hat off, it is much easier to prove the act – the taking of the hat – than to prove the person’s desire to take the hat.

To overcome this difficulty, there is a common law principle that permits tries of fact to infer that individuals intended the natural consequences of their actions. In the Supreme Court of Canada case, R v Théroux, Justice McLachlin (as she then was) stated that “subjective awareness of the consequences can be inferred from the act itself, barring some explanation casting doubt on such inference.”

Returning to the hat example. If the ostensible hat thief was charged with theft, considering Théroux, it would be permissible for the trier of fact to conclude that the shopper intended to steal the hat. However, the accused would be permitted to adduce evidence that casts doubt on such an inference. That evidence could be as simple as the accused explaining that she has never stolen anything in her life, that she had a busy day, she completely forgot the hat was on her head, and that she accidentally walked out of the store without paying for it.

Knowledge

Knowledge is the awareness of a fact or circumstance. Knowledge is subjective. As such, it focuses on what the accused knew, not what the accused should have known.

For example, the offence of assault. Section 265 of the Criminal Code states as follows:

Assault

265 (1) A person commits an assault when

(a) without the consent of another person, he applies force intentionally to that other person, directly or indirectly;…

Application

(2) This section applies to all forms of assault, including sexual assault, sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party or causing bodily harm and aggravated sexual assault.

Consent

(3) For the purposes of this section, no consent is obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of

(a) the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant;

(b) threats or fear of the application of force to the complainant or to a person other than the complainant;

(c) fraud; or

(d) the exercise of authority.

Accused’s belief as to consent

(4) Where an accused alleges that he believed that the complainant consented to the conduct that is the subject-matter of the charge, a judge, if satisfied that there is sufficient evidence and that, if believed by the jury, the evidence would constitute a defence, shall instruct the jury, when reviewing all the evidence relating to the determination of the honesty of the accused’s belief, to consider the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for that belief.

There are two mens rea components in the s. 265 assault provision – the intentional application of force, and an absence of consent.

The intentional application of force deals with intent.

Absence of consent is concerned about the accused persons knowledge that the application of force is not consented to. This requires the court to prove that the accused knew that the complainant did not consent to the application of force.

Just like with intent, knowledge can be inferred from an individual’s actions. If the accused walked into a bar, walked up behind a patron that was sitting at the bar and punched the patron in the back of the head, the trier of fact would likely find that the patron did not consent to the application of force.

Conversely, if the complainant was taunting the accused, asking the accused to fight, and telling the accused that he wanted to fight, and the accused struck the complainant. The trier of fact would likely conclude that the complainant consented to the application of force.

Wilfull Blindness

Wilfull blindness attributes knowledge to individuals. In this regard, wilfull blindness is a substitute for knowledge. Wilfull blindness is not an attempt to say that the accused should have known something. Rather, as the Alberta Court of Appeal noted in R v Briscoe, wilfull blindness “serves to override attempts to self-immunize against criminal liability by deliberately refusing to acquire actual knowledge.”

Wilfull blindness imputes the accused with knowledge. It arises in circumstances where the accused virtually knows what is happening, but they intentionally decline to secure that knowledge.

In Briscoe, the accused drove the victim to a remote area, he then stood by and watched while the victim was raped and murdered. The Crown argued that the accused was wilfully blind to the murder of the victim. In finding that the Crown had established wilfull blindness, the Alberta Court of Appeal stated:

[20] It is important to keep in mind that the application of the wilful blindness doctrine focuses on the accused’s state of mind. Moreover, it applies where the accused not only had a suspicion, but virtually knew the critical fact, and intentionally declined to secure that knowledge….

[21] Because of this, the knowledge that is attributed to an accused is subjective in nature… Wilful blindness is not premised on what a reasonable person would have done, but requires a finding that the accused, with actual suspicion, deliberately refrained from making inquiries because he or she did not want his or her suspicions confirmed. It is only on that basis that the doctrine may be applied. If it is, the knowledge imputed is the equivalent of actual, subjective knowledge.

Recklessness

The final subjective standard is recklessness. Recklessness is not the same as knowledge, nor is it tantamount to knowledge (as wilfull blindness is). Recklessness, although subjective, is something less than knowledge. It is focuses on the accused’s awareness and his irresponsibility.

Recklessness exists where the accused is aware that his conduct could bring about the prohibited criminal act, but he persists despite the risk. Thus, there are two components to a finding of recklessness, they are as follows: (1) awareness of a risk or danger and (2) persisting with the act despite the risk.

Objective Mens Rea

Objective mens rea looks at the accused’s actions from an objective standard – it focuses on what the accused should have known. Objective mens rea focuses on negligence offences, where the accused’s actions fail to meet the standard of a “reasonable person.” When an individual’s’ actions fall below the “reasonable person” standard, the individual will be found to have satisfied the objective mens rea requirement. A reasonable person is someone who is:

- reasonable, informed, practical and realistic;

- the person is right-minded; and

- dispassionate and fully apprised of the case.

If an individual’s actions fall below the “reasonable person” standard, they may be guilty of a criminal offence. In determining whether an individual’s actions fallow below the “reasonable person” standard, judges rely on a modified objective test.

There are two types of modified objective tests. The first is the marked departure test. The second is the marked and substantial departure test.

The marked departure test requires less of a departure from norms than the marked and substantial departure test. As a result, crimes that have a marked departure as the mens rea tend to be less serious than crimes that require a marked and substantial departure.

The marked departure test requires the judge to determine whether the accused’s behaviour is a “marked departure” from what a reasonable person would have done. If the judge finds that the accused’s actions were a marked departure, the accused has satisfied the mens rea requirement of the offence.

Some offences, such as criminal negligence causing death, require the accused’s actions to be a marked and substantial departure from what a reasonable person would do. The difference between marked departure and marked and substantial departure is the degree to which the individuals actions depart from what a reasonable person would have done. As the name suggests, the marked and substantial departure test requires a greater departure from norms than the marked departure test.

As was the case with the marked departure test, if an individual is charged with an offence where the mens rea requires a marked and substantial departure, and the judge finds that the accused’s actions were a marked and substantial departure, the accused has satisfied the mens rea requirement of the offence.

Conclusion

Mens rea is the “guilty mind.” Mens rea can be either subjective or objective. Subjective mens rea focuses on what was actually going on in the accused’s mind. Subjective mens rea can be intent, knowledge, wilfull blindness, or recklessness. Objective mens rea focuses on what the accused should have known. Objective mens rea considers whether an individuals actions were a marked, or a marked and substantial departure, from what a reasonable person would do.

Blog written by Matthew Browne

Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer based in Calgary. If you have been charged with a criminal offence or are a suspect in a criminal investigation, call today for a free, no obligation consultation.