Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer, serving Calgary, Okotoks, Airdrie, Strathmore, Cochrane, Canmore, Didsbury, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge and Turner Valley.

Hearsay is an area of law that far too many lawyers simply fail to understand. It isn’t complex, yet it leads to countless mid-trial applications and unnecessary delay.

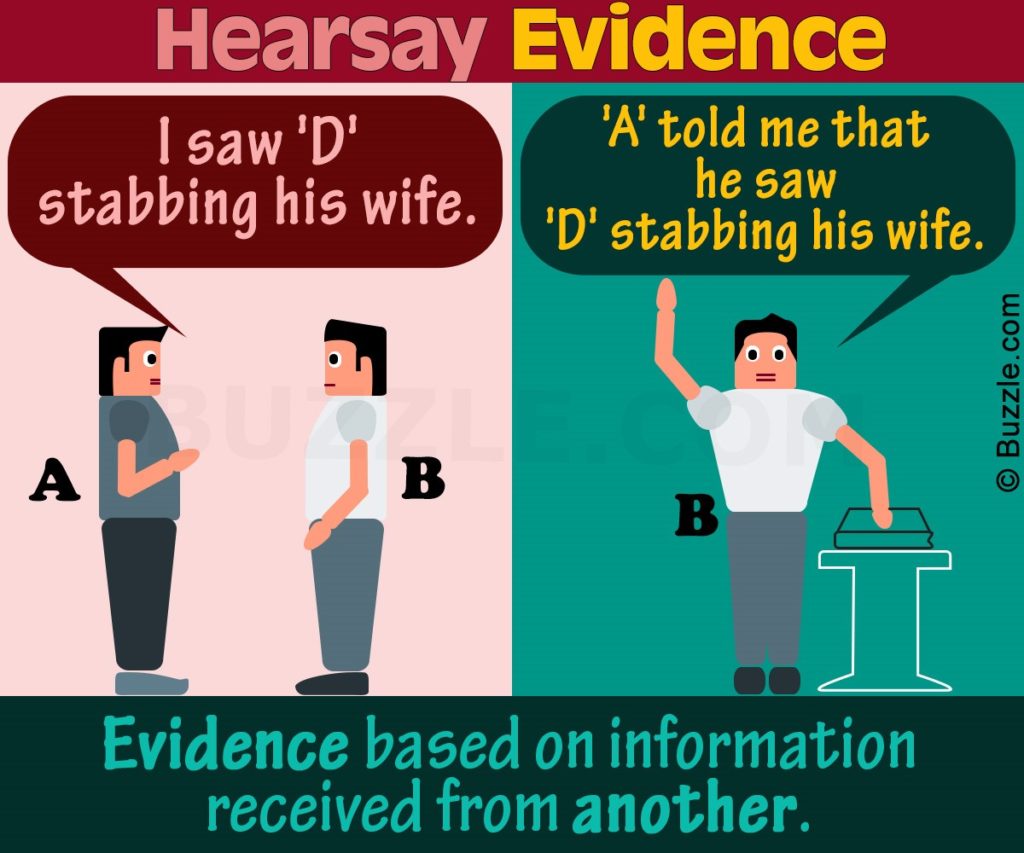

Hearsay is an out of court statement offered for the truth of its contents. The general rule is that hearsay is inadmissible. Hearsay includes verbal and non-verbal statements as well as implied statements.

Exceptions to the Hearsay Rule- The Principled Approach

Hearsay evidence will be admissible under the principled exception to the hearsay rule if it can be shown to be sufficiently necessary and reliable. Necessity is typically made out if the declarant is not reasonably available, e.g. if they are deceased, incompetent, untraceable, or if testifying would be unacceptably traumatic. To make out reliability, a trial judge applying the principled approach will look for evidence of threshold reliability: balance-based evidence showing that the hearsay is “sufficiently reliable to overcome the dangers that arise from the difficulty of testing it”.

The Eight Most Common Exceptions to the Hearsay Rule:

- Prior Inconsistent Statements –the Evidence Act provides: “a witness may be cross-examined as to previous statements made by him or her in writing, or reduced into writing, relative to the matter in question”. If the statement is inconsistent, the recording of the prior inconsistent testimony may be required to be produced to the judge.

- Prior Identifications –out-of-court identifications made by a witness may be admissible if: a) the witness repeats the identification in-court; or, b) if the witness does not repeat the identification, but is available to be cross-examined.

- Prior Testimony –evidence given in a prior proceeding by a witness is admissible for its truth in a later proceeding provided:

- the witness is unavailable;

- the parties are substantially the same;

- the material issues to which the evidence relates are substantially the same; and,

- the person against whom the evidence is proffered had an opportunity to cross-examine the witness at the earlier proceeding.

- Prior Convictions –are admissible for the purpose of establishing prima facie that the person committed the offence. If the witness denies the convictions, proof may be presented of the convictions.

- Admissions of a Party –a helpful rule is that “anything the other side ever said or did will be admissible so long as it has something to do with the case”. This may include verbal statements, acts, statements of others adopted by the opposite party, and statements by coconspirators in furtherance of a conspiracy. Admissions may be formal (pleadings, agreed statements of fact, etc.) or informal (conduct, silence, etc.)

- Statement Against Interest by Non-Parties – in order to qualify for this exception, the statement: a) must have been contrary to the declarant’s proprietary or pecuniary interests when it was made; b) the declarant must be unable to testify; and, c) the declarant must have personal knowledge of the facts stated.

- Declarations in the Course of Duty –at common law, such declarations, verbal or written, are admissible for their truth where the declaration are: a) made reasonably contemporaneous; b) in the ordinary course of duty; c) by persons having personal knowledge of the matter; d) who are under a duty to make the record or report; and, e) there is no motive to misrepresent the matters recorded. This exception has been incorporated into provincial and federal legislation.

- Res Gestae or Spontaneous Utterances –the statement is made by the declarant in such circumstances that allow some truth-value to be assigned to the statement. The statement must be made at the precise time of the event or sensation that the declarant is commenting on, and not after e.g. present sense of impression or physical condition.

Substantive and Procedural Reliability

In R v. Bradshaw, the Supreme Court of Canada clarified that there are two methods for establishing threshold reliability: substantive reliability and procedural reliability. Procedural reliability addresses the court’s core concern about hearsay: the fact that it cannot be tested through cross-examination. In procedural reliability, hearsay evidence will be let in if there is a “functional substitute for trial testing” present. A partial example would be a complete and unadulterated videotaped statement. The trial judge may be able to use the videotape to observe the witness’s demeanor and assess their accuracy and sincerity, a key component of the cross-examination process which is lost when admitting hearsay evidence.

Alternately, reliability may be made out through establishing substantive reliability. This is made out when the statement is considered “inherently trustworthy,” providing such a high degree of comfort to the trier(s) of fact that even a “skeptical caution” would look on the statement as reliable. An example from the case law of substantive reliability is a natural, swift and specific utterance by a young child, who lacks a motive to lie and has no anticipation of penal consequences, implicating the accused in wrongdoing. In the eyes of the court, this type of evidence is prima facie reliable enough to be admitted despite the fact that it is hearsay.

In Bradshaw, the Crown sought to admit Mr. T’s video re-enactment through a third pathway: a combination of procedural and substantive reliability indicia. Though uncommon, this option for establishing reliance is available for submitting parties willing to take it on. At trial, the judge found numerous examples of both procedural and substantive reliability. The re-enactment was voluntary, free-flowing, incriminating and made after Mr. T had received legal advice. The statement was also corroborated by extrinsic evidence. On these grounds, combined with the corroborative evidence, the trial judge let the evidence in.

The Appeals

On appeal, the British Columbia Court of Appeal found that the trial judge relied too heavily on the corroborative evidence in deciding that the hearsay video was reliable. The corroborative evidence included forensic evidence that confirmed Mr. T’s detailed descriptions of the murders, and evidence that Mr. T had accurately described the weather on the night in question. The BCCA pointed out that while submitting parties are entitled to rely on corroborative evidence to show threshold reliability, the corroborative evidence offered by the Crown did not actually implicate Bradshaw in the murders. In fact, the corroborative details were equally consistent with the possibility that Mr. T was lying about Bradshaw’s participation. Several additional facts of the case supported this alternate explanation. First, Mr. T refused to take the stand at Mr. Bradshaw’s trial, thus depriving the trial judge of the opportunity to assess his sincerity. Second, Mr. T gave inconsistent accounts of Bradshaw’s involvement in the murders. Third, Mr. T had a significant motive to lie to reduce his own culpability. Finally, Mr. T was a Vetrovec witness, one who “[could not] be trusted due to his unsavoury character”.

Majority

Given these facts, both the BCCA and the SCC believed there was a strong possibility that Mr. T had lied about Bradshaw in his video statement. Key to the decision was the fact that both courts continued to harbor suspicions about the veracity of Mr. T’s evidence despite the presence of the corroborative material. According to the SCC, this meant that the corroborative information was unhelpful in assisting the trial judge in assessing reliability. In essence, the corroborative evidence failed because it was unable to eliminate alternative explanations for Mr. T’s statement. The purpose of admitting corroborative evidence is to establish the reliability of the hearsay statement itself. If the corroborative evidence is consistent with the idea that the statement is true, but is also consistent with the idea that the statement is false, it adds nothing of value to the trial process. In fact, it risks jeopardizing the trial by distracting and/or misleading the finder(s) of fact. To that end, the SCC reiterated its ruling in Khelawon that hearsay is sufficiently reliable “if it overcome[s] the dangers that arise from the difficulty of testing it”. The specific hearsay danger posed by Mr. T’s evidence was that Mr. T was lying (as opposed to being genuinely mistaken, an equal but different concern). Given that the danger was not overcome by the corroborative evidence—it was equally likely that Mr. T had been lying even given the corroboration—it also failed because it did not eliminate the dangers posed by the hearsay evidence.

Ultimately, the SCC clarified that the corroborative evidence would have only been useful to the trial judge if it demonstrated that the only likely explanation for the video statement was Mr. T’s truthfulness about Mr. Bradshaw’s participation. Essentially, corroborative evidence should only be used if it significantly curtails—indeed almost eliminates—the likelihood that the hearsay statement is inaccurate. To that end, the SCC said that trial judges must consider alternative (even speculative) explanations that might account for the hearsay statement, before letting it in.

Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer based in Calgary. If you have been charged with a criminal offence or are a suspect in a criminal investigation, call today for a free, no obligation consultation.