Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer serving Calgary, Okotoks, Airdrie, Strathmore, Cochrane, Canmore, Didsbury, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge, Grand Prairie and Turner Valley.

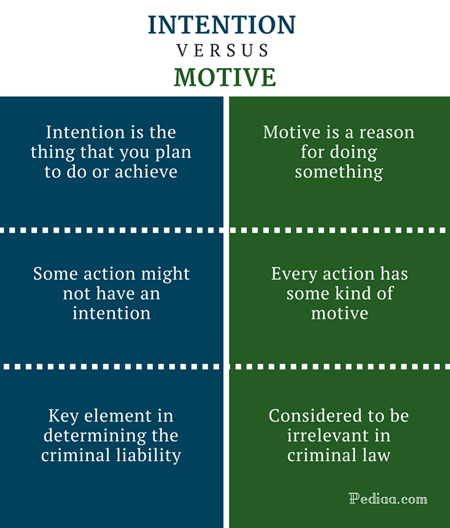

Intent and motive focus on an individual’s mental state. Intent is concerned about an individual’s decision to carry out a specific action. Motive is concerned about the underlying reason for carrying out that action. The two concepts are often conflated. However, in criminal law, it is important to understand the difference between the two, as one – intent – can be an essential element of an offence, while the other – motive – is not.

Intent

In R v W(A), Judge Blacklock of the Ontario Court of Justice noted that over the years courts have defined intention in multiple ways. In some circumstances, intention has been confined to the notion of purpose. In other circumstances, it has been expanded to include consequences foreseen as “substantially” or “practically” certain. Finally, other courts have said that intention includes recklessness, which is where an individual sees a risk and proceeds anyway.

Judge Blacklock provided a helpful summary of intent in paragraph 38 of W(A).

In everyday speech, we may be said to have intended an outcome if we expect it to occur and consciously proceed to act in a way that we expect will bring about the result.

Intent can be specific or general. Specific intent focuses on the act, the social policy underlying the offence and the complexity of the reasoning process, while general intent focuses only on the act. It can be difficult to discern the difference between specific and general intent. This was noted by Moldaver J of the Supreme Court of Canada in R v Tatton:

[21] Although the labels “general intent” and “specific intent” are entrenched in Canadian law, they are not particularly helpful in describing the actual mental element required for a crime: Daviault, at p. 123; Bernard, at p. 854 (per Dickson C.J., dissenting). The mental element of specific intent crimes is no more “specific”, in the everyday sense of the word, than the mental element of general intent crimes. Rather, as we shall see, the distinction lies in the complexity of the thought and reasoning processes that make up the mental element of a particular offence, and the social policy underlying the offence.

[22] This Court’s decision in Daviault is the leading case on the distinction between general and specific intent crimes. Unfortunately, it has not resolved the confusion surrounding this issue. The general/specific intent dichotomy continues to perplex counsel and trial courts alike. It has been criticized as illogical and as leading to “arbitrary and inconsistent results from court to court, offence to offence and jurisdiction to jurisdiction”: G. Ferguson, “The Intoxication Defence: Constitutionally Impaired and in Need of Rehabilitation” (2012), 57 S.C.L.R. (2d) 111, at p. 123. See also T. Quigley, “Specific and General Nonsense?” (1987), 11 Dal. L.J. 75; D. Stuart, Canadian Criminal Law: A Treatise (5th ed. 2007), at pp. 437-39; M. Manning, Q.C., and P. Sankoff, Manning, Mewett & Sankoff: Criminal Law (4th ed. 2009), at p. 389; S. H. Berner, “The Defense of Drunkenness — A Reconsideration” (1971), 6 U.B.C. L. Rev. 309, at pp. 333-34.

[23] The confusion surrounding the general/specific intent distinction is part of a larger problem that has plagued the Canadian criminal law for decades. Regrettably, the Criminal Code often provides no clear direction about the required mental element for a given offence. (Emphasis Added.)

General Intent

General intent is a lower mens rea than specific intent. General intent only requires a conscious doing of the prohibited act. General intent distinguishes “intentional” actions from “accidental” actions.

For example, if a man is riding on a subway and he intentionally touches a woman’s breast, he has intentionally touched that woman. On the other hand, if a man is riding on a subway that comes to an abrupt stop and the man falls over and accidentally touches a woman’s breast while he falls over, he did not intentionally touch that woman.

In the first case, the man could be guilty of sexual assault. In the second case, although the man committed the actus reus of sexual assault, he did not possess the mens rea for sexual assault as he did not intend to touch the woman’s breast.

Specific Intent

Specific intent requires the conscious doing of the prohibited act coupled with a specific state of mind. Alberta Court of Appeal Justice Paperny provided a helpful summary of specific intent in her dissenting judgement in R v SJB:

[56] The dichotomy was further refined by the House of Lords in D.P.P. v. Majewski, [1976] 2 All E.R. 142, where “specific intent” and “basic intent” were contrasted. Lord Simon of Glaisdale recognized that “specific intent” had been used in three different senses. First, when a particular state of mind compounded with a prohibited conduct constitutes an offence. Second, as an “ulterior intent”, when a state of mind contemplates consequences beyond those defined in the actus reus. Third, Fauteux J.’s description of specific intent in George as intention applied to acts in relation to their purposes. Lord Simon concluded at 154, “where the crime is one of ‘specific intent’ the prosecution must in general prove that the purpose for the commission of the act extends to the intent expressed or implied in the definition of the crime.” (Emphasis added.)

For example, the offence of attempted murder is a specific intent offence. Section 239 of the Criminal Code states that “Every person who attempts by any means to commit murder is guilty of an indictable offence.” This means that to be guilty of attempted murder the Crown must prove that the accused had the “specific intent to kill.” No lesser mens rea will suffice.

Distinguishing General Intent from Specific Intent

By reading an offence in the Criminal Code, it can be difficult to determine whether an offence is specific or general intent. Justice of Appeal Paperny’s decision in SJB is helpful on this point:

[62] Three tests have been offered to determine the difference between specific and general intent offences. The first, described as a purposive test, was (as quoted above) set out in George:

In considering the question of mens rea, a distinction is to be made between (i) intention as applied to acts considered in relation to their purposes and (ii) intention as applied to acts considered apart from their purposes. A general intent attending the commission of an act is, in some cases, the only intent required to constitute the crime while, in others, there must be, in addition to that general intent, a specific intent attending the purpose for the commission of the act.

In D.P.P. v. Morgan [1975] 2 All E.R. 347 at 363, Lord Simon similarly defined specific intent in contrast to crimes whose definition expresses a mens rea which does not go beyond the actus reus. He offered the example of assault as not a specific intent offence because the consequence is closely connected with the act.

[63] The second, described as an ulterior intent test, was described by Lord Simon in Majewski at 154 as a “state of mind contemplating consequences beyond those defined in the actus reus”. Assault causing bodily harm would be an example where the accused must have the ulterior intent of causing bodily harm. Lord Simon considered ulterior intent to be only one type of specific intent but did not capture all specific intent crimes since murder is a specific intent crime not defined by contemplation of consequences extending beyond the actus reus.

[64] The third test, described as recklessness, is intended to capture specific intent offences where recklessness cannot suffice as the necessary mental element. Murder meets this test.

Motive

Motive focuses on the reason for someone’s actions – what prompted the person to act. Motive is distinct from purpose, which is the “thing intended.” Criminal law has little interest for the motive behind a person’s actions. This is because focusing on the motive behind the person’s actions would not eliminate the actus reus or mens rea of the offence. Motive simply provides context to why an individual acted in a certain way.

For example, consider a fight between two individuals – Mark and Gary. Mark and Gary used to be best friends. Then Mark found out that his wife was having an affair with Gary. This infuriated Mark. As soon as he learned about the affair, he drove over to Gary’s house to confront him. When Mark arrived, Gary was mowing his front lawn. A verbal altercation transpired which ultimately culminated in a fist fight. Mark threw the first punch and ended up being charged with assaulting Gary.

To get a conviction, all the Crown needs to prove is that Mark intentionally punched Gary. Mark’s reason for doing so – although relevant in providing context to the nature of the assault – is not relevant when it comes to proving the elements of the offence.

Intent vs Motive

To distinguish intent and motive consider the following example. One evening, a stockbroker receives insider information that the value of XYZ Stock is going to plummet in three days after news about an environmental scandal is released. The stockbroker is on the verge of receiving a promotion, all he needs is one more “big move.” The next morning, the stockbroker sells all of XYZ Stock.

In this case, the stockbroker’s general intention was to sell XYZ Stock. The stockbroker’s specific intention was to rely on the insider information to sell XYZ stock. The stockbroker’s motive for selling the stock was to get a promotion.

Conclusion

Intent and motive are both concerned about an individual’s mental state. Intent can be an essential element of a criminal offence. Motive is not. Intent is either general or specific. General intent is an individual’s intention to carry out an act. Specific intent is an individual’s intention to carry out an act in light of the social policy underlying the offence and the complexity of the reasoning process. It can be difficult to distinguish general intent from specific intent. In this regard, Justice of Appeal Paperny’s comments in SJB are instructive. Finally, motive is distinct from intent. Motive does not focus on an individual’s actions, rather, it focuses on the underlying reason for carrying out those actions.

Blog written by Matthew Browne

Cory Wilson is a criminal defence lawyer based in Calgary. If you have been charged with a criminal offence or are a suspect in a criminal investigation, call today for a free, no obligation consultation.